Pomodoro vs. Flowtime: What Cognitive Science Says About Studying Smarter

When you’re knee-deep in school assignments, midterms are around the corner, and you still have to work your two shifts this weekend, time becomes precious when you’re in university.

With such little precious time, the time we can commit to studying (using the RSA Method) must be effective and efficient. What’s more, is that often when we find the time in our busy schedules to study, it can be difficult to convince ourselves to get going and take that first step and open up our books.

In the last several years, many students have heard of and used time management techniques such as the Pomodoro Technique, but we explore in this article why this may not be the best option anymore.

The Hidden Limit of Human Attention

When I was in first-year university, one of the very first videos I ever watched about studying was a video by Marty Lobdell called Study Less Study Smart. The thing that stuck out to me from this video was the drawing he did on the board of a students’ attention span. In highschool, I had always felt that drop off of attention, but I didn’t realize how physiologically NO ONE can study for hours straight. This video radically changed how I approached learning, and ignited passion for more research on effective studying techniques.

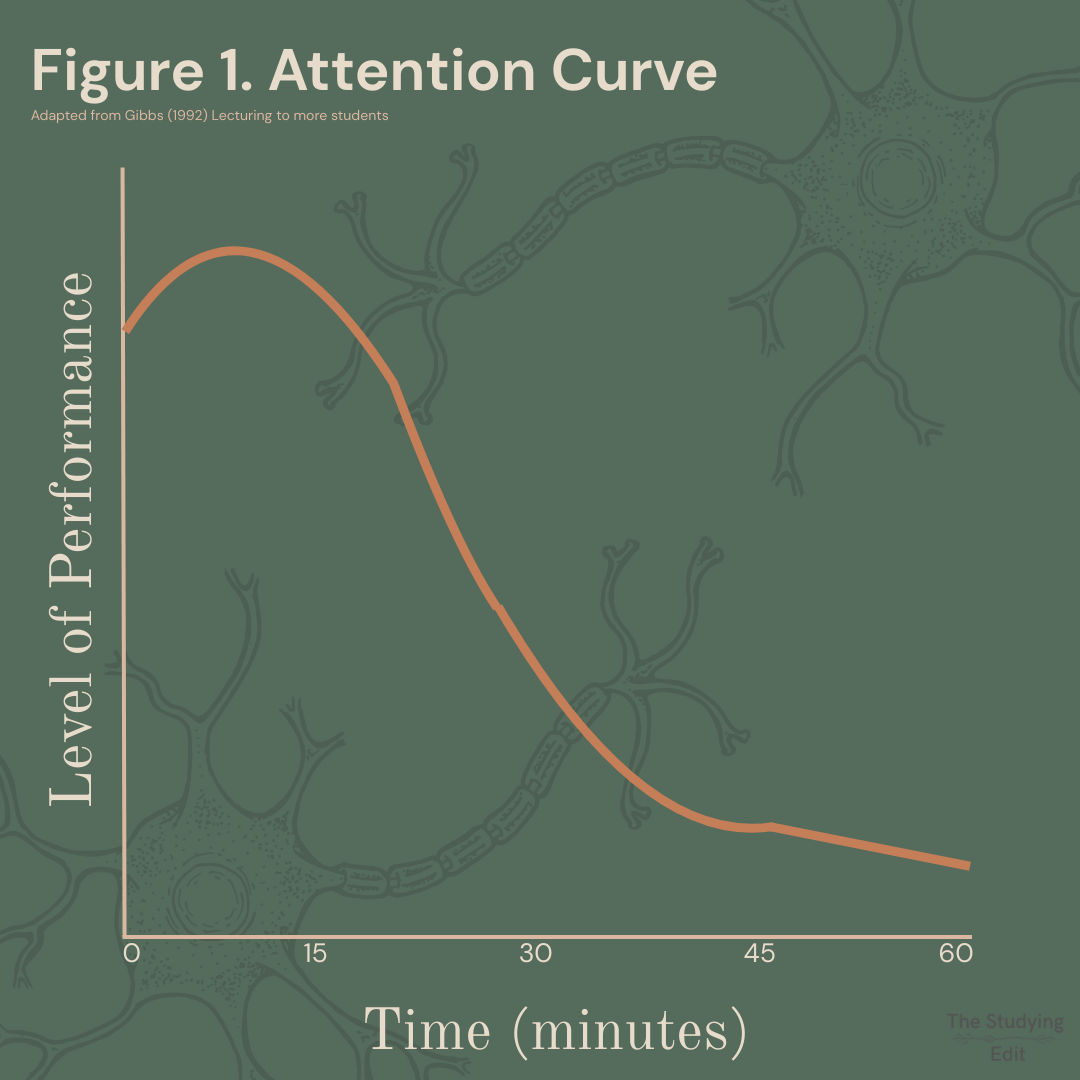

In Figure 1, you can see an attention curve (adapted from Marty Lobdell’s lecture). This figure demonstrates the average attention span of an adult. Attention is sustained for the first 30 minutes or so, and then we see a dramatic drop in attention shortly after. Marty, in the video, makes the excellent point that there is no reason to keep studying after this 30 minute mark because it’s not as effective.

So are we just supposed to study for 30 minutes a day?

Not quite, but science supports studying for approximately 30 minutes at a time. Research has suggested that by studying in discrete “sets” that are staggered by small breaks, you are allowing your brain to rest and “reset” before studying again, bringing that attention curve back up to its original position (Vallesi et al., 2021, Almalki et al., 2020).

The Pomodoro Technique

In recent years, a popular technique that students have adopted for time management is the Pomodoro Technique. The Pomodoro Technique was developed by Francesco Cirillo in the 1980’s. It’s name comes from a tomato (pomodoro in Italian) shaped kitchen timer that was used to keep track of the study-on and study-off times. In this technique, the student is instructed to study for 25 minutes, then take a 5 minute break. This cycle continues for a total of 4 times, and then a longer 15 minute break is taken before the cycle starts again.

The Pomodoro Technique works great for many students, specifically helping with productivity (Almalki et al., 2020). It’s much easier to tell yourself to sit down and study for 25 minutes than it is for 2 hours.

However, recent studies have shown that students who used the Pomodoro Technique fatigued faster than those who did not (Smits et al., 2025). The authors suggest that the Pomodoro Technique interrupts the flow state of students and that this segmentation and interruption can negatively affect studying.

Flow State

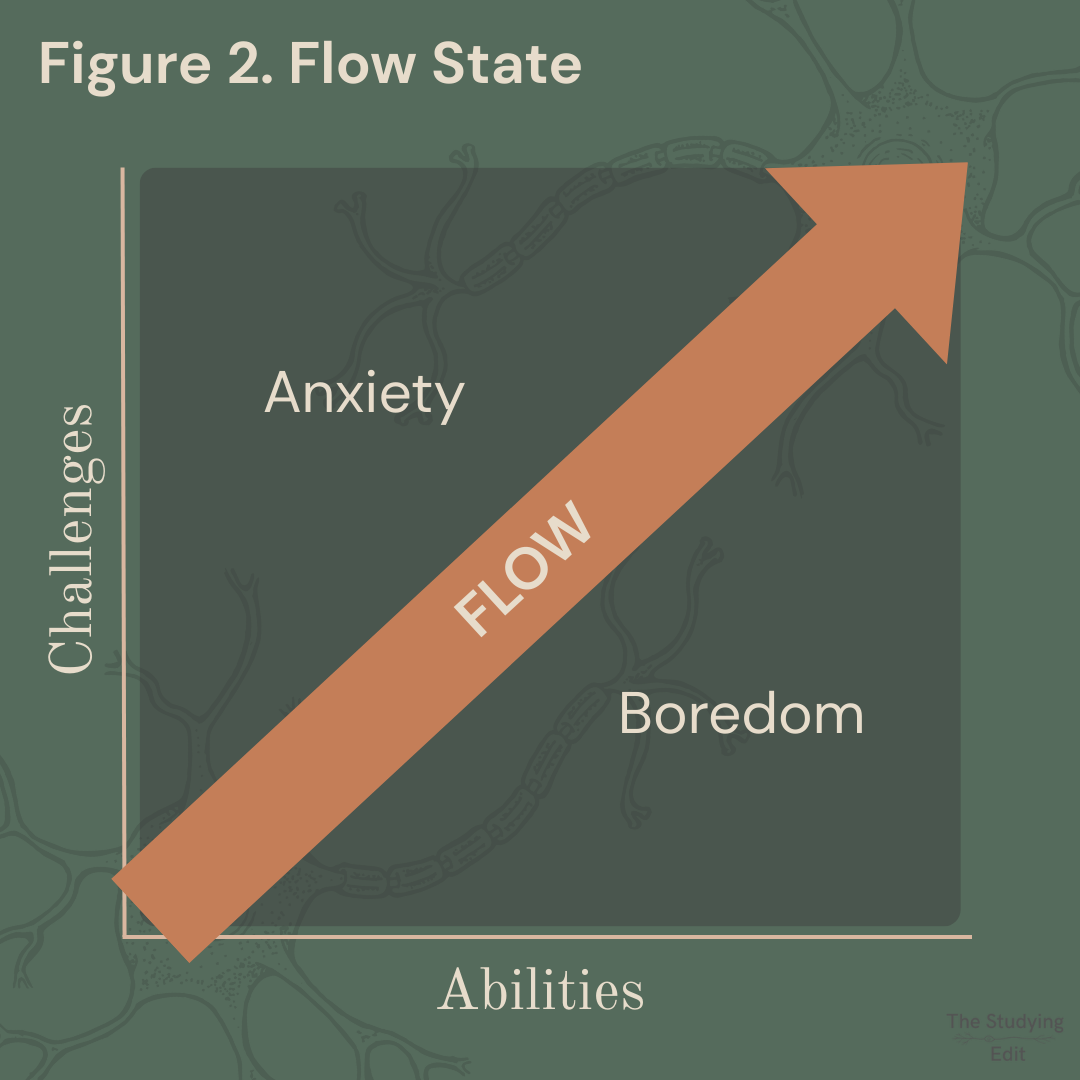

Flow state is a term coined in 1989 by Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre where they described a state of mind where the challenge-skill balance influences the quality of the individual’s experience and that there is a “pocket” where the challenge-skill balance is just right. When people find this balance (flow state), they are able to enjoy the task more and be more effective at the task. Often, flow state is referred to through the lens of sports, but in the original 1989 article, the authors looked at flow state through the lens of being at work vs. leisure activities. The authors found that individuals were more likely to achieve flow state at work because of more difficult challenges and opportunities to use higher-level skill sets.

The Flowtime Technique

An alternative to the Pomodoro Technique is the Flowtime Technique. The Flowtime Technique can be traced back to Zoe Read-Bivens in 2016. This technique is designed to account that a flow state may be reached by students while studying, and if constrained to a 25 minute timer, they may be missing out on valuable studying productivity by stopping. In this technique, students are still encouraged to record their start and finish times, and time a 5 minute break (give or take, depending on the length of the study block). Importantly, there is no timer telling students when to stop studying. These study blocks may last 45 minutes, or just 15 minutes. It is up to the student to self-access and self-monitor their mental acuity and determine when it’s time for a break.

Once students understand the function of the Flowtime Technique, it is very easy to implement into their studying routine. However, without the rigidity of the Pomodoro timer, the Flowtime Technique is more susceptible to procrastination. With my students, I have found that an approach to this kind of time management can mirror the Pomodoro Technique at first - tell yourself that for this first study block, you’re going to study for 20 minutes. This is a very approachable amount of time for our brains; however, if we reach flow state and we end up studying beyond 20 minutes, we don’t stop at the timer. A studying habit tracker or log is a great solution for students to track the amount of time they are studying, and how long of a break they get based on the amount of time of the studying block. I have attached a free template that students are welcome to use to track their studying using the Flowtime Technique.

The biggest hurdle I see students face time and time again is just getting started. It is the classic application of Newton’s First Law of Motion - an object in motion stays in motion, and an object at rest stays at rest. If you find yourself on your phone, putting off studying, don’t think about the 4 hours of studying that need to be done. Think of that first 20 minutes only, and once you get going and you reach your flow state, you’re an object that is staying in motion!

Citations

Almalki, K., Alharbi, O., Al-Ahmadi, W., & Aljohani, M. (2020). Anti-procrastination online tool for graduate students based on the Pomodoro Technique. In P. Zaphiris & A. Ioannou (Eds.), Learning and Collaboration Technologies. Human and Technology Ecosystems. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 12206, pp. 133-144). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50506-6_10

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56(5), 815.

Gibbs, G. (1992). Lecturing to more students. Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council: Oxford Centre for Staff Development.

Pomodoro® Technique. (n.d.). Pomodoro® Technique – Time management method. Retrieved December 30, 2025, from https://www.pomodorotechnique.com/

Smits, E. J. C., Wenzel, N., & de Bruin, A. (2025). Investigating the effectiveness of self-regulated, Pomodoro, and Flowtime break-taking techniques among students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070861

Taskade. (2024, August 29). Flowtime technique explained: A complete guide. Medium. Retrieved December 30, 2025, from https://taskade.medium.com/flowtime-technique-explained-a-complete-guide-aea41c734cdc

Vallesi, A., Monti, T., & McIntosh, A. R. (2021). Age differences in sustained attention tasks: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(6), 1805–1820. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01908-x